I bet you’ve heard rumors about it already. I bet word has already gotten upwind of you and drifted down to your eyes and ears about the effects of “that ‘love’ brain chemical”. Maybe in your prenatal class, in a prenatal mental haze, you remember hearing something about “a hormone involved in birth and nursing”. You might have even seen the latest fad of nasal spray and perfume designed to “increase trust” and “feelings of love and contentment” in whomever gets a nose-full.

There is a fair amount of hype going on at present in the weedy fields of developmental- and neuro-psychology, and parenting support circles around the globe concerning the neuro-transmitter Oxytocin. Some are calling it “the moral molecule”. Some say triggering it increases empathy, trust, and relational cohesion. Some say doses administered to certain people on the autism spectrum can increase their social cognition. Some champions even herald it as the biochemical end to all human warfare.

Me? I just think it’s an integral part of parenting our children the way our biology intends.

Oxytocin is one of the chemicals women’s brains release during labor. It helps make uterine contractions stronger — which is why chemists somewhere invented the synthetic drug, Pitocin, to administer to women struggling to have productive contractions. After the baby is born, Oxytocin is vitally involved in both milk-release and “the nursing buzz” that many women get when they breastfeed. It’s also the main neurotransmitter we are experiencing when we have those fuzzy, warm, connective moments with our babies, when it feels like the world dissolves and time stands still and you feel so much love for that little being that you could just die in the immensity of it all, and you never want to tear your gaze away… ❤ ❤ ❤

After the baby is born, Oxytocin is vitally involved in both milk-release and “the nursing buzz” that many women get when they breastfeed. It’s also the main neurotransmitter we are experiencing when we have those fuzzy, warm, connective moments with our babies, when it feels like the world dissolves and time stands still and you feel so much love for that little being that you could just die in the immensity of it all, and you never want to tear your gaze away… ❤ ❤ ❤

Hey… Hey! I’m still trying to tell you something here! Quit triggering Oxytocin with your baby memories and pay attention! 😉

Oxytocin is the primary harbinger of in-group trust and love and cooperation in our brains. We feel it when we fall in love. We feel it when we experience love. We feel it in all the ways we express love — from simple thoughts of those who mean the most to us, from just being in proximity to each other, from gentle, meaningful touch, from hugs, kisses, and sex, and from getting married, sharing things that matter to us, having fun together, and expressing trust in one another.

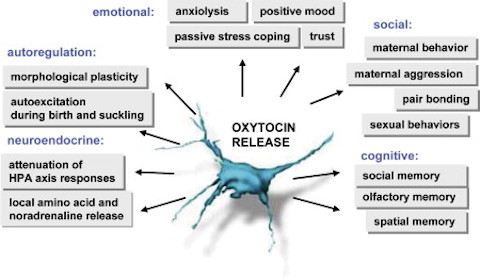

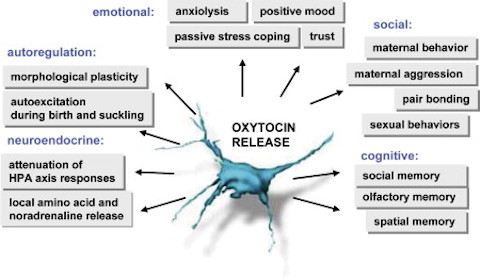

Actually, there is a host of beneficial responses the brain has in the presence of Oxytocin:

Oxytocin is, interestingly, also different for different brains. We don’t understand a lot about it yet, but what we do know is that different people in differing contexts experience Oxytocin in variable ways. The current thinking seems to be that for the individual, the way in which one has developed plays a role in how she processes Oxytocin, effecting even whether she has as many receptors in place for absorbing the neurochemical once it’s released. Daniel A. Hughes, PhD, and Jonathan Baylin, PhD, in their important book, Brain-Based Parenting, put it this way:

So, if in your parental brain, the activities of parenting light up your nucleus accumbens through a chain effect involving both oxytocin and dopamine [the learning- and craving-focus neurotransmitter], then you are going to experience being a parent differently from someone’s brain who does not do this, or doesn’t do it as strongly as your brain does. Furthermore, the density of receptors for both oxytocin and dopamine in a parent’s brain depends, in part, on how that parent was parented, on the quality of care he or she received early in life. Good care promotes the “expression” of the genes for oxytocin and dopamine receptors, and this means that a child’s well-cared-for brain makes more of these receptors.

(p32)

If a person doesn’t get sound, secure, nurturing parenting, her brain doesn’t develop as many receptors for Oxytocin, and won’t process it the same way, and, therefore, may not have as much access to the feelings that it otherwise engenders. That is, she will likely feel less connection in social relationships, less joy in loving moments, and less empathy and care for her own children — and likely more stress and feelings of inadequacy in all of the above.

The other major factor in how Oxytocin expresses itself in an individual brain seems to have to do with the social environment in which the person finds himself. If he’s not with an in-group with which he can readily identify, or the event involving the group is one in which the subject feels stress and/or competition, then other neurochemicals can thwart, subvert, or derail the Oxytocin effect. Cortisol, the primary stress neurotransmitter can totally shut down Oxytocin release. Testosterone can also trump an Oxytocin cascade. Paul J Zak, author of The Moral Molecule describes a test he did at a colleague’s wedding measuring Oxytocin levels in the blood of various people at the wedding both before and immediately after the ceremony:

[The bride] Linda’s own level shot up by 28%. For the other people tested, the increase in oxytocin was in direct proportion to the likely intensity of their emotional engagement in the event. The mother of the bride? Up 24%. The father of the groom? Up 19%. The groom himself? Up 13%…and on down the line. But why, you may ask, would the groom’s increase be less than his father’s? Testosterone is one of several other hormones that can interfere with the release of oxytocin, and the groom’s testosterone level, according to our blood test, had surged 100%! As the guests admired Linda in her strapless bridal gown, he was the alpha male.

(The Wall Street Journal; 4.27.12; “The Trust Molecule”)

You may, of course, now be wondering why this matters to you. As a parent, we’re just trying to get through our days without losing it, right?! We’re just trying to get from point A to B with kids in tow and our wits about us and nothing catching on fire! We’re just trying to keep our sh!t together, and help our kids keep their sh!t together — and still keep liking each other. So why would it matter how any one of us is prepared to or how any particular scenario would effect the manner in which we release, receive, and process brain chemicals?!

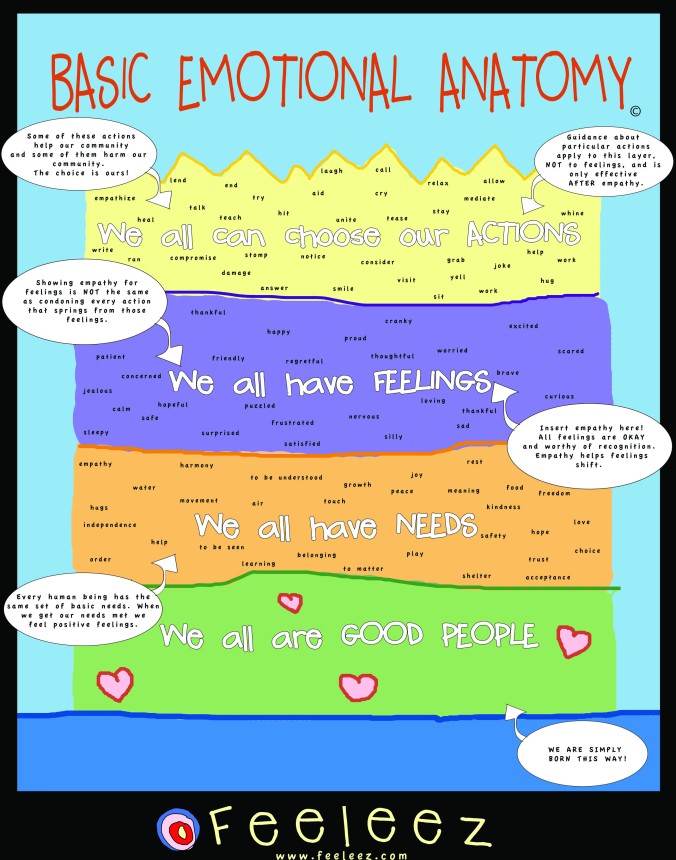

Well — here’s the deal. In any relationship scenario, all humans are navigating a brain dance between attraction and repulsion. In attraction states of mind, we are drawn to approaching, open to being approached, and interacting in a socially conducive manner. In repulsion states of mind, the opposite is true, we seek to avoid, to be avoided, and to create aversion. We balance these two states on both a conscious and unconscious level. Our Amygdala, resting but always alert in our limbic systems, uses “neuroception” to perceive before we can consciously know we’re perceiving whether or not we are in danger. This is why, when startled, we leap before we know why. In terms of our relationships, we have the option to use our conscious knowledge of these mechanisms to keep our brains from tricking us into triggering defensive, or even o-ffensive, states of mind.

In terms of parenting, and borrowing from Hughes and Baylin again:

“The goal, then, is to stay in the open state of social engagement as much as possible… This is quite challenging for all parents because the process of interacting with children is inherently stressful, and inevitably, at times, triggers defensive feelings that are not consistent with the caring feelings we want to have. The social engagement system is only activated when we feel safe enough being near another person.”

(p16-17)

As it turns out, the Amygdala, a structure we don’t have much conscious control over, can tell if we’re in danger and either activate or inhibit our fight, flight, freeze, or appease reactions.

If the neuroception system does not detect any real threat, it activates our social approach system, engendering a sense of safety and promoting trust between people… When we are able to activate this basic “approach” system as a parent, the rest of the parenting process, including the ability to experience intense pleasure from being with our children, turns on and fosters the development of enduring bonds with our kids.

(p18; my italics)

The Amygdala inhabits a starring role in the play between how open and approachable we (and our kids) feel, and how closed and defensive we feel. But as the directors of our minds, we don’t hold a heckuva lot of sway over this lead character. The Amygdala is, however, a/effected by — you guessed it — Oxytocin:

The medial [that is, the central interior portion of the] amygdala… is involved in rapid, automatic switching between these two responses of approaching versus avoiding. One of the ways that this switching is orchestrated without the involvement of higher control process is through the release of oxytocin into the medial amygdala by pleasant experiences with other people, including “good touch” and warm, friendly voices. The amygdala has receptors for oxytocin and when these receptors are “occupied”, this has a quieting effect on the amygdala. In this way, oxytocin helps to inhibit the defensive, avoidant reaction system, enabling the social engagement system to stay on.

(p20; my italics)

And the Amygdala’s is not the only brain function readily malleable to the warming effects of Oxytocin:

“All right already — wrap up all the neuro-babble, and tell us what the heck you’re getting at, Nathan!!” you may be saying…

There’s a few things, not of all of which are mentioned explicitly above, that I want you to be able to walk away with today:

- Our brains can either help or hinder us in this whole parenting gig. If we’re working with our biology and with our children’s developing biology, our brains are built to help us work together, and feel great about it in the process. If we’re working against our biology, our brains can make it nearly impossible to do the delicate dance of parenting conscientiously.

- Parenting effects brain development. The individual’s receptivity to Oxytocin has a lot to do with the conditions under which the brain was developed. Our brains wire Oxytocin reception (including those receptors used to quiet the Amygdala) based on feedback from the brain’s assessment of the environment and the care-givers. Safer-feeling surroundings, more nurturing parenting, and greater emotional assistance in times of duress, tell the brain to wire for greater Oxytocin reception, and thereby, better overall resilience. Since we want our kids to feel connected to us, and further, as they develop, to feel socially safe and open (and not paranoid and avoidant) — we want to help them grow a healthy Oxytocin reception system. This means using it — sending out those waves of love, showing them we trust them, helping them have those warm feelings of connection — and keeping their environs safe-feeling enough that their brains don’t have any reason to hold back from developing in an optimal manner.

- We can use Oxytocin to assist us in parenting:

By soothing our babies’ and toddlers’ and young kids’ social systems with warmth, touch, nursing, rocking, connection, empathy, and emotional-processing assistance when they are upset, we can help them turn off their defensive system and return to feelings of calm and trust and the mutual identification that primes them for feeling greater connection with us in the future. This can help us both feel more like working with each other in the moment, but also fosters a deepening sense of ongoing “co-operation” and “same-team-ness”, as I like to call it.

By soothing ourselves in times of personal turmoil — whether it’s feelings of inadequacy as a parent, feelings of disconnection from our children, or even non-parenting-related feelings of stress about money or work, etc. — using techniques like self-empathy, intentional optimism, and redirection; and/or restorative measures like meditating, mindful exercise, massage, sex, fun, laughter, etc.; we can use our own neurological systems to empower us to be better, more caring, more empathetic, more creative and resilient parents.

- We can start from right where we are. We can’t go back and completely redevelop our brains, though there is much that we can do immediately. So far as we currently understand, we can’t naturally grow ourselves more Oxytocin receptors. We can, however, help rewire our habits around releasing Oxytocin and our sensitivity to it. We can practice getting calmer before parenting interactions, thinking positive thoughts, remembering happier, more connected parenting moments. And we can use what we know about our approach and avoidance systems to choose paths to being more open, accepting, and connective with our kids. We can also help them to grow healthy brains that are nurtured toward working happily with us, and feeling good about it while they do — just by using Oxytocin release!

- And here’s how:

1) Touch — hold your baby, skin-to-skin is best, smooth her cheeks, massage his limbs; pet your kids, hug them often (especially before potentially stressful events), and cuddle them for no reason, 30 seconds is generally enough for a hug to trigger Oxytocin release in both participants; then also snuggle them when they are upset and/or need a good cry, because you’re supporting healthy neuro-processing, even before they are calm enough to begin releasing Oxytocin again.

2) Play — having fun together has too many benefits to list here, but the point for the moment is that it works double to release Oxytocin in the moment, and prime the developing brain for better reception in the future.

3) Empathy — using it with our kids is Oxytocin triggering Oxytocin. When we employ empathy to understand each other, we create an Oxytocin circuit. This increases mutual empathy and paves the way for more empathetically-oriented brain wiring in both participants. In times of emotional upset and/or disagreement, use empathy to understand, express your felt empathy as understanding, and let the Oxytocin take hold of you both before proceeding.

4) Create Safe Space — dedicate your household and your parenting to instinctual and emotional safety. Make it feel safe for your kids to trust you, to bring you their woes, and to rely on your stalwart connection. Make it feel safe (in all aspects) for your kids to be in the world, or at least the home-space, as they are, no matter how they are being at the moment, and regardless of who else is sharing the space. Make certain they know that they are significant in your eyes, that they belong, and that their needs will be met.

- And if you feel like you need some Oxytocin yourself:

1) Enjoy — pick anything/anyone you love and really pay close attention to what you love there. Take time to be there. If it’s a subject, study it. If it’s an object, hold it. Take someone you like to dinner or coffee and chat with sustained eye contact. Stare into your baby’s face. Get into whatever/whomever it is. If all you have is your thoughts, they will do just fine, just use them to imagine the above. It only takes a minute or so for your brain-chemistry to join in, but the longer the better.

2) Touch — get some! Go get a hug from someone you like (for 30 seconds at least!). Encourage your partner to snuggle you. Schedule a short massage. Give yourself a vigorous foot rub. Or any other self-pleasuring… It’s all for the sake of helping you be a better parent! 😉 And so you feel better, yourself, for that matter.

3) Sex — if you can, do. If you don’t have someone to do it with, as above, you can still release a healthy dose of Oxytocin taking care of yourself. Remember, this is to help you be the best human you can be!

4) Media — use your social and entertainment media time to feel good. Pick movies and shows and books that make you laugh or feel sexy or remember the power of love. Go to all your social sites and have fun with distant friends and connections (though less at the expense of interacting with loved ones in proximity…). Don’t just get online to get pissed about how awful everything in the world is, balance your input wisely, for Oxytocin’s sake!

5) Pet your pets — it’s as simple as that. Every time you spend a couple minutes giving rubs to your favorite furry friend, you give yourself a healthy shot of the good stuff.

6) Tell loved ones that you love them — use the words, look deep into their eyes or at a picture while you have them on the phone, and say it loud and proud — I LOOOVE You.

If you want more of the how-to, both in terms of Oxytocin release and using other brain mechanisms for better parenting, skim through the posts I linked to above. And these two.

I love knowing that our brains are designed to help us be the best, most successful parents we can possibly be. I love knowing that although we can’t change everything about how our brains were grown, we can change how we relate to what our brains are capable of doing. And I love knowing that we can use our brains to help our children grow theirs to be even more capable than we are of both leading healthy happy lives, and being gentle, nurturing parents!

One day, one moment, one interaction at a time, using our helpful brains, and dear, sweet Oxytocin, we can expand our abilities to feel exceptionally loving, happy, and thriving in the experience of parenting. And at the same time, in those same moments and tiny interactions, we can help our kids grow more joyful, connective, and cooperative brains, too! What a nice package, eh?

*

Be well, my fellow brain-arborists. I [Oxytocin] you!

*

Feeling as jazzed as I am about Oxytocin and burning (via Dopamine release) to know more? Check out the links below for an Oxytocin-primer:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=URpuKgKt9kg

http://psychcentral.com/lib/about-oxytocin/0001386

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702304811304577365782995320366

http://www.psychologytoday.com/blog/the-moral-molecule/201311/the-top-10-ways-boost-good-feelings

http://www.medicaldaily.com/oxytocin-love-hormone-fuels-romance-how-your-brain-works-when-youre-love-269067

http://io9.com/5925206/10-reasons-why-oxytocin-is-the-most-amazing-molecule-in-the-world

http://www.mindfulmamma.co.uk/2012/11/birth-oxytocin/

http://www.amazon.com/Oxytocin-Parenting-Susan-Kuchinskas-ebook/dp/B0081T8AAO/ref=sr_1_1?s=books&ie=UTF8&qid=1413426886&sr=1-1&keywords=Oxytocin+Parenting

http://www.apa.org/monitor/feb08/oxytocin.aspx

http://www.wjh.harvard.edu/~zaki/bartzEtAl_2011_revOXT.pdf