Ok, look. I’ve broached this subject over a 100 times in various forums, blogs, journals, social media posts — you name it. And I usually spend a lot of time coddling us all as we navigate the tender history of our own parenting and our parents’ parenting, and I do my best to make an honest but gentle critique of this major flaw in our current child-raising paradigm. But it’s gotten to the point where when I see another credentialed practitioner espousing the merits of “praising the right way” or “employing natural consequences”, I start banging my forehead on my palm.

We have got to get this tired notion out of our heads, friends. We’ve got to quit our addiction to Behaviorism.

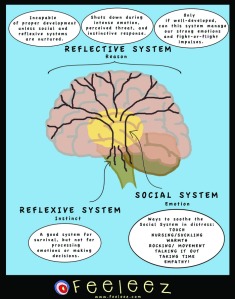

It should be pointed out, for those of you who’ve never heard the story, that Behaviorism — a pseudoscience based on the notion that human behavior is a malleable commodity to be controlled and harvested for economic advantage — was designed to make subjects do whatever they were told. Not simply to do what was preferable, or intelligent, or kind, but anything that was commanded and associated with reward and/or punishment. And frankly, it’s very effective in certain cases, to a certain extent, and more so with adults than children. But it just so happens to have us all focussing on the least important thing about us humans.

We are not just what we do. Nor are we merely valuable for what someone else can make us do.

Consider the implications of that, if you will, for just a moment…

When it comes to raising our children — we want them to know, and understand, and feel it in their bones, that we love, and value, and cherish them for no other reason than that they are. That they exist. Not because of what they do, or will do if we turn the right screws. And because we want them to never even question their worth to us, and to develop a healthy sense of self-worth — we absolutely have to stop dealing with them solely on the level of how to make them do just what we want.

We have been tricked into thinking that A+B=C, when in fact, A+B only ever equals (A+B). When we take a child (A) and add Behavioristic manipulation (B), we do not automatically get cooperation (C) and we certainly don’t guarantee getting a controlled or “good” child. All we ever assure ourselves under that equation is that we get a manipulated child. That child not only learns to manipulate others in her life, she also learns that none of us matter except inasmuch as we allow ourselves to be what someone else wants us to be. I hope as you read it to yourself, you hear/d how dangerous that is.

The raw truth is that we don’t actually want our children to grow up to be easily controlled. So we had better stop training them for that way of life and that variety of perspective on themselves.

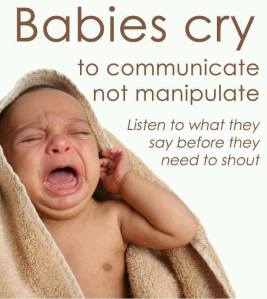

“So then,” you may wonder, “how the H do we get our kids to do what we want??” And the answer is we ask. That’s it. That’s all there is to the magic of cooperation. That’s our only (dignified, nonviolent) tool for getting what we want with anyone else in the world. Why would we use any other method with our kids? Why should we? Unless we screw it up by trying to manipulate them all the time, our children are the most likely humans on the planet to cooperate with us — far and away more willing to do what we ask far more often than anyone anywhere ever. And while we’re at it, maybe we want to have more reasonable expectations in terms of how much we ask them to do and how much they’re willing to do.

No one on Earth ought to live life being willing to do whatever we ask of them regardless of what it is or how they feel just because we ask. Not even our own kids.

If we want cooperation from our kids — because why would we really want more than that — then we would do well to focus on co-operating with them. When we co-operate, we’re not just complying or expecting compliance, we’re actually working together — operating in company. No one is trying to make anyone else do stuff all the time, and no one is just doing for the other all the time either. We’re doing together — we’re meeting needs together, we’re accomplishing goals together, we wading through all the things that come up for each of us together. The idea that we should rely on our children to be or do more than that is simply an unreasonable expectation that Behaviorism has hoodwinked us into chasing.

And when we ask, and they say “No,” or whine and stall, or throw themselves bodily onto the floor — and they will just because they are human and they are young — our job is not to double-down on trying to force or bribe them into respectfully performing our will. As leaders in the co-operative field of the family, our job is to work together in order to be able to work together! If one part of the unit is having trouble functioning normally, we help it! We don’t override it, or ignore it, or coax it to just go ahead and operate as is.

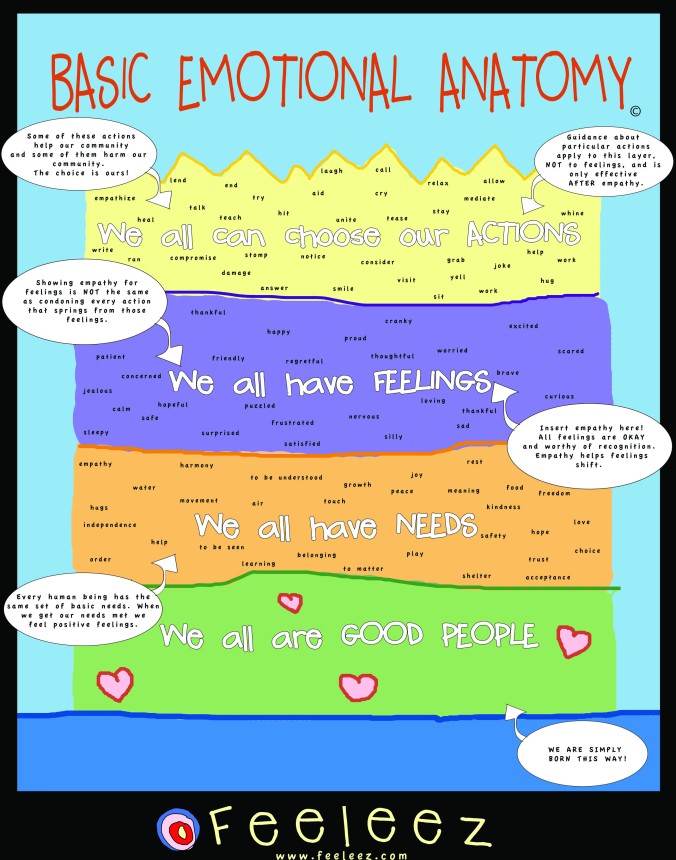

In order to address breakdowns in co-operation, we get curious. We look for the feelings beneath what our children are doing or not doing. We look to see if there are underlying needs they are attempting to meet.

And when we find something down there below the behavioral surface — because when they won’t do what we ask, it’s almost always due to some uncomfortable emotion(s) or unmet need(s) they’re feeling — we pause the “-operation” and focus on the “co-”. We connect. If there are feelings blocking our children’s ability to work with us, then we look at those together, and offer our children empathy and touch as we hear and make room for their emotions. If there are, as yet, unmet needs lurking below the disquieting feelings, then we look to help our children address those. Before we expect that they will be able to operate again.

When we address feelings — whether it is manic exuberance or riling anger or tender anxiety — we remove the burden blocking our children’s emotional drive to work with us. And when we focus our efforts on helping our children meet their needs — rather than on securing their unflinching compliance — we remove the obstacle(s) to their willingness to help us meet our needs. When we co-operate with them, then they naturally cooperate with us. C+C=(C+C)! It’s as simple as that.

If you find yourself needing more convincing on how terribly behavior-focussed parenting serves us all (parents and children alike), I encourage you to delve into the works of Alfie Kohn. Unconditional Parenting and Punished by Rewards are his two most notable tomes on the subject, and should be enough to convince even the most empirically-minded among us. You can also order a DVD of Kohn delivering an excellent address on Unconditional Parenting at the UP link above, for those of you who can’t stand to ever read another parenting book in your life.

The bottomline of all this is simply that we don’t need to control our children’s behavior to make them “good” people. We just need to understand them and support them in being their best selves.

So please, my dear fellow parents, let’s all decide to be done with critiquing and manipulating how our children behave. And instead, let’s get laser-focussed on co-operating to meet needs and to process those underlying feelings, before we ask our kids to do anything else. We’ll all get much further if we agree to go together.

For those of you who want more information or who want support while navigating the subtleties of co-operation, I happily invite you to come and get it!

*

Be well.

cozy up, and often the best spot is under a blanket, naked on your bare chest; it might seem perfunctory, but try it, and you’ll see magic (especially if you also use chest-to-chest time in between upsets…).

cozy up, and often the best spot is under a blanket, naked on your bare chest; it might seem perfunctory, but try it, and you’ll see magic (especially if you also use chest-to-chest time in between upsets…).